(Last updated 2/12/2022)

I have grouped Saturn, Uranus and Neptune together because, from my viewpoint, they present a similar problem. Their sidereal periods are longer than the time interval that I have been making measurements for, so that the methods that I used to find the periods of the other planets don’t work so well. For Uranus and Neptune especially I am extrapolating its behavior over quite a short fraction of an orbit.

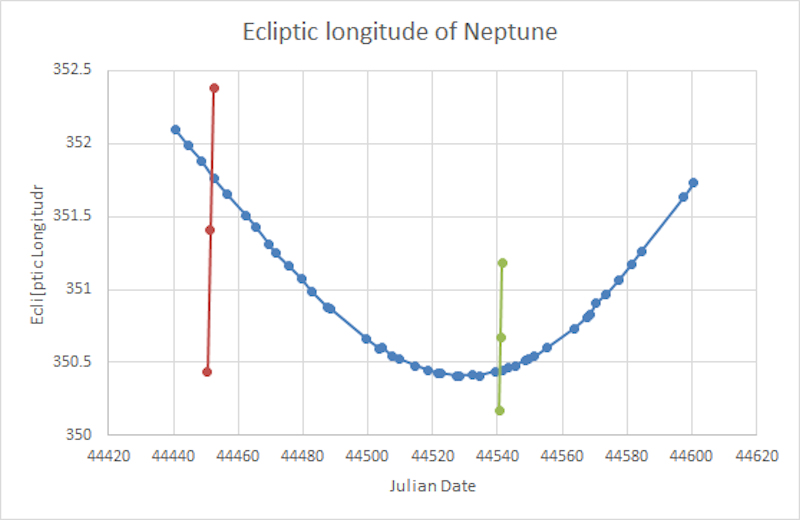

I tracked Neptune through its opposition in September 2021 and continued until it got very low in the twilight in February. Here is the measured loop:

My fitting program gives values for the average distance, R, of Neptune from the Sun during the loop and the time T it would take it to complete a revolution if it kept moving at its present speed. The values I get are R = 30.1 ± 0.2 a.u. and T = 163 ± 3 years. These are both a bit smaller than the semimajor axis of 30.23 a.u. and the sidereal period of 164.79 years, but I expected that because Neptune is moving (very slowly) towards perihelion.

For Saturn and Uranus, I did pull out from my old notebooks a more-or-less casual observation from several years earlier, which I finished up making a lot of use of, but the values I calculate come out rather higher than the handbook values. It is just my bad luck that both planets have been moving through aphelion. I have made some new observations beyond the results in my book, but the gain in precision is very slow.

Here is a summary of my measurements of the oppositions of Saturn and Uranus:

Saturn

Date Julian day (DJD) Longitude at opposition

1/27/2006, 14:23 UT 38743.1 127.5°

3/22/2010, 0:29 hrs 40257.52 181.2707°

4/3/2011, 23:12 hrs 40635.47 193.8506°

5/23/2015, 1:31 hrs 42145.56 241.6343°

6/3/2016, 7:29 hrs 42522.81 253.1207°

6/27/2018, 13:32 hrs 43277.06 275.8580°

The first result is a bit less accurate than the others.

For Uranus

Date Julian day (DJD) Longitude at opposition

5/15/1980, 12:hrs UT 29355 233°

9/23/2010, 17:05 hrs 40441.21 358.606°

9/26/2011, 0:37 hrs 40810.53 2.59°

10/15/2016, 11:37 hrs 42656.98 22.51°

10/24/2018, 0:58 hrs 43394.54 30.565°

The first observation is very approximate. The date is uncertain by ±30 days and the longitude by ±7.5°

One way to use these numbers, very similar to what I did in several places in my book, is to plot graphs in Excel and ask for linear trendlines. For example, I can plot the longitude at opposition versus the Julian day, and from the slope I can calculate the sidereal year. The values that come out from the slopes of the lines are not significantly different from the values that I calculated by hand, given in chapters 5 and 7 of the book.

More or less as an experiment, I tried another approach. It has the advantage that it actually needs only the measurements taken during one retrograde passage. For each passage, my least-squares fitting program gives values of the distance of the planet from the Sun at opposition, and a number that I called the instantaneous period. This is actually just a way of parameterizing the angular velocity. For uniform circular motion, the angular velocity is related to the period by ω = 2π/T and it was easier for me to continue using T as the fitting parameter than to bring in ω as a new parameter. Kepler’s second law is that the planet sweeps out equal areas in equal times and that is equivalent to saying that d²ω or d²/T is constant. d is the distance of the planet from the Sun at opposition. The fitting program also prints out a value of d²/T. Here are the results for the two planets.

Saturn

Year distance time d²/T

2010 9.58±0.04 29.5±0.2 3.11±0.04

2011 9.72±0.07 30.0±0.4 3.15±0.06

2015 9.97±0.02 32.22±0.09 3.085±0.012

2016 10.04±0.02 32.65±0.15 3.086±0.019

2018 10.063±0.009 32.767±0.054 3.090±0.007

For Uranus

2010 20.1±0.2 93.0±2.0 4.33±0.12

2011 20.0±0.1 93.1±1.3 4.30±0.08

2016 19.86±0.05 90.9±0.5 4.34±0.03

2018-19 19.84±0.04 90.3±0.4 4.36±0.03

As I pointed out in my book, the values of d²/T for each planet are equal within the uncertainties, and this does verify Kepler’s second law. They should be approximately equal to a²/P, where a is the semi-major axis and P is the sidereal period. There is also a factor of √(1 – e²). I could assume this is close enough to 1 compared with the precision of my values, but I shall take it into account at the end of my analysis of the results, and also for Mars on its page. The new step I am taking now is to apply Kepler’s third law. If a is measured in astronomical units and P is measured in Earth years, which are the units used in the tables here, Kepler’s third law is that P² = a³. Then the ratio a²/P is just equal to the square root of a or the cube root of P. That is

a = (a²/P)², P = (a²/P)³.

The catch with this approach is that it does rely completely on the exactness of Kepler’s laws, which we know is not quite valid, but I am assuming that the departures from the laws are smaller than my uncertainties. The advantage, as I said, is that all this method of analysis needs is data from one retrograde passage so you could get these numbers in just a few months observations.

The results for Saturn are fairly complete so I can try a rather elaborate analysis. Rather than simply using the most precise of the values, I can take a weighted average of all of them to find a best value of d²/T of 3.0905 ± 0.0073. I could again ignore the factor of √(1 – e²) and square this value to get an estimate of the semi-major axis, a. But if I assume that the largest value I have measured for d, 10.063 au, is close to the aphelion distance I can find an estimate of the eccentricity e and hence apply the correction factor. Of course, this changes the answer I get for a, so I have to repeat the calculation, and keep repeating it until the answer stops changing. I did this iteration in a TrueBasic program, but in fact three or four iterations are enough. The final values I get are

a = 9.57 ± 0.04 au, P = 29.6 ± 0.2 yrs, with e = 0.051 ± 0.005.

Taking the 2018 distance to be close to aphelion implies that the aphelion longitude is close to 276° so that the perihelion angle is about 96°.

This gives me a complete set of orbital parameters for Saturn. As I have written for Mercury and Venus, the only number I am missing is the mass. But, of course, I should be able to measure the mass of Saturn by tracking the orbits of one or more of its moons. Is this a future project? Keep an eye on this space.

Well, I did it! I tracked Saturn’s brightest moon, Titan, for ten weeks in the Fall of 2020 and fitted a curve to the results to give me values for the sidereal period, P, and the radius, r, of its orbit. The values I found were r = (1.20 ± 0.02) × 1E6 km, and P = 15.93 ± 0.02 days. From these I can calculate a mass for Saturn of (5.4 ± 0.2) × 1E26 kg.

Now to do the analysis for Uranus. The best estimate of d²/T is 4.349±0.019. This used directly would give values for a and P of 18.91 and 82.28. If I make an iterated correction to this assuming that my largest value of the distance is close to the aphelion distance I get my best values

a = 19.0 ± 0.2 au, P = 83 ± 1 yrs, with e = 0.0574 ± 0.0128.

The value for the eccentricity is rather higher than the handbook value but within my uncertainty. The value of 358.6° for the longitude at opposition that I measured in 2010 would correspond to a longitude of perihelion of 178.6°. With my present equipment I have no chance of observing any moons of Uranus in order to find its mass.